As part of our upcoming revision of the 2019 ISCAID guidelines for diagnosis and management of bacterial urinary tract infections (UTIs) in dogs and cats, we recently did a systematic review to determine if cranberry supplements reduce or help treat urinary tract infections (UTIs) in dogs and cats. Our conclusion was… we have no idea.

There’s very little regulation of nutraceuticals like cranberry supplements. If products are not being marketed as drugs, there are few to no requirements to prove efficacy (or even safety). So budgets for these products tend to go to marketing, not research, resulting in many products that are widely used with no supporting data whatsoever. Some might work. Most probably do nothing (except maybe make the owner feel better because they are doing something).

Our systematic review aimed to answer four questions:

Does cranberry or cranberry component administration

- reduce the incidence of bacteriuria in dogs and cats?

- reduce the incidence of bacterial cystitis in dogs and cats?

- improve resolution of bacterial cystitis or bacteriuria in dogs and cats?

- reduce the recurrence of bacterial cystitis or bacteriuria in dogs and cats?

We found that little has been published. That either means little research has been done on these products, or that research has been done and not been published, possibly due to publication bias.

Publication bias is a significant concern. People are more motivated to publish “positive” studies (that show the effect they were hoping for), and manufacturers are more likely to bury studies that didn’t show the effect they wanted, or showed no effect. We recently evaluated publication bias in regard to probiotics for gastrointestinal disease in dogs and cats (Weese 2025) by looking at research abstracts on probiotics that were presented at conferences, compared to which ones were ever published in a journal. Overall, 5/7 (71%) abstracts that reported a clinical effect were published, compared to 1/5 (20%) that did not. We also have no idea how many studies may have been done and never presented in any form.

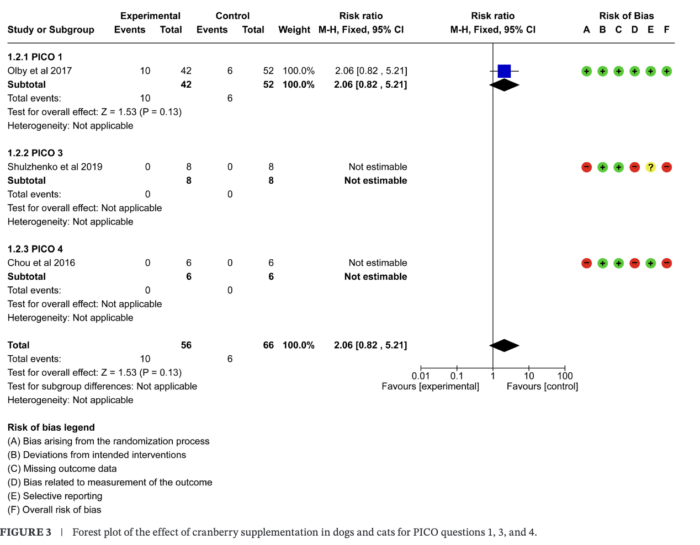

Regarding cranberries, we found three studies, but they were of variable quality. One was quite good and looked at cranberry for prevention of urinary tract infection in dogs with spinal cord disease. The other two were quite weak and only included a small number of animals (12 and 16 respectively).

So to answer the questions in above with respect to administration of cranberry or cranberry component, does it:

1) reduce the incidence of bacteriuria in dogs and cats?

The stronger study looked at this in dogs with spinal cord disease. The study was stopped early because there was a numerically higher incidence of bacteriuria (positive urine cultures) in dogs that got the cranberry supplement. Clearly futile.

2) reduce the incidence of bacterial cystitis in dogs and cats?

4) reduce the recurrence of bacterial cystitis or bacteriuria in dogs and cats?

One weak study with only 6 dogs per group looked at cranberry for prevention of recurrent cystitis, so it covered both of these questions. It didn’t show an effect as no dogs in either group developed cystitis during the study period.

3) improve resolution of bacterial cystitis or bacteriuria in dogs and cats?

One study investigated the impact of a cranberry and orange supplement plus an antibiotic (enrofloxacin) compared to antibiotic alone in cats with cystitis The sample size was small (8 cats per group) and no conclusions could be drawn because all cats in both groups responded to treatment (not surprising since they all got an antibiotic).

For any review of an intervention, safety is always an outcome that is evaluated as well. No studies reported safety data.

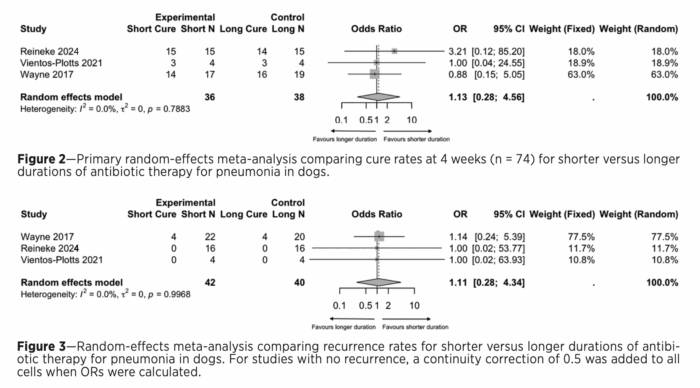

For those interested in meta-analysis and data, the overall Forest plot is below:

This does NOT necessarily mean cranberry supplements don’t work. It means we don’t have any data showing that they do work.

- Cranberry might be effective, but the right studies haven’t been done.

- Cranberry might be effective in certain animals and certain situations, but those haven’t been studied.

- Cranberry might be effective at different doses or with different preparations.

…Or it might in fact be that cranberry is not an effective aid in any way for UTIs in dogs and cats.

We have no idea if any commercial supplements work since none have any published supporting data, so it’s buyer beware. These products are probably harmless, but it’s hard to say if they are useful at all.